In our series of letters from African writers, Ghana’s Elizabeth Ohene writes that George Floyd, whose killing has sparked a global debate about race relations, has been immortalised in the West African state that was central to the transatlantic slave trade.

We do funerals well here in Ghana. When it comes to the rituals, music, clothes and ceremonies that accompany them, I can safely say that nobody does them better.

As I watched the funeral of George Floyd on television, I needed no reminding that most African-Americans can trace their origins to West Africa and grand funerals come easily to them. Or they have had to organise these painful funerals of their people so regularly that they have become well practised.

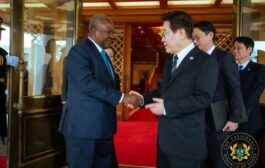

During the Houston funeral on Tuesday, there was a reference to the message of condolence sent to Mr Floyd’s family by Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo.

It was also mentioned that at the president’s request, Mr Floyd’s name had been permanently mounted on the wall of the Diasporan African Forum at the W.E.B. Du Bois Centre in Ghana’s capital, Accra.

This was done at a moving ceremony, organised by the Ghana Tourism Authority last week, in memory of Mr Floyd, who was killed on a street in Minnesota when a police officer knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes.

Ghana marked in spectacular scale the year 2019, the 400th anniversary of the start of the transatlantic slave trade.

President Akufo-Addo declared 2019 the Year of Return, with a special invitation to all Africans in the diaspora, especially the descendants of slaves, to come to Ghana, either to visit or even to live permanently.

Many of the forts and castles through which the slaves were transported are still standing in Ghana and they remain a source of trauma and emotional distress for visiting black people.

When the Floyd murder story broke, many people took it personally here.

Before the outbreak of coronavirus, we had been looking forward to a big influx of visitors from the African-American community.

Six black state attorneys general from the US had been in Ghana in March as part of the Beyond the Return initiative, and were guests at our Independence Day celebrations on 6 March.

Among that group was Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, who is now in charge of prosecuting the accused in the Floyd case.

When the GTA organised the memorial, it was personal and it showed.

Elizabeth Ohene, Ghanaian journalist

The haunting music of the dirges on the flutes signalled that Mr Floyd was one of our own and we were sending him off to our forefathers”

A crucial part of funerals in Ghana are the colours worn. They would try to describe the person who had died and how.

So the colour scheme at Mr Floyd’s memorial was predominantly red and black to show a man had been cut down in the prime of his life, and his death had been unnatural and unexpected.

The haunting music of the dirges on the flutes signalled that he was one of our own and we were sending him off to our forefathers.

It has been interesting for us here to note that our famous distinctive fabric, the kente, has also become part of the George Floyd story.

When senior US Democratic lawmakers “took a knee”, in a dramatic gesture to honour Mr Floyd, they all wore kente stoles.

Ghanaians are intensely proud of the kente fabric. Once upon a time, the kente, or kete as it is called in my part of the country, was an almost exclusive fabric worn by royalty and rich people.

It is hand woven and each design has a name and tells a story.

With the passage of time and the intervention of the Arts Faculty of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in the second city Kumasi, the kente was transformed and popularised for use among young people in particular.

It remains the fabric for special occasions but we have now found more and varied uses for it.

When the University of Ghana started issuing its own degrees following independence, it put kente strips on the boring academic gowns that it had been using when it started life as a University College of London University.

Kente stoles soon became the symbol of graduation and other commemoration events, with the appropriate words woven into the strip. You may therefore have Class of 2000, or Year of Return, or even The Best Dad kente stoles.

We are happy to have African-Americans adopt the kente to emphasize their African roots and if others want to use it to show their solidarity, we have no complaints.

I suspect that some enterprising weavers will soon bring a kente design named I Can’t Breathe, and we shall wear it to remember and celebrate the life of Mr Floyd.

Source: BBC