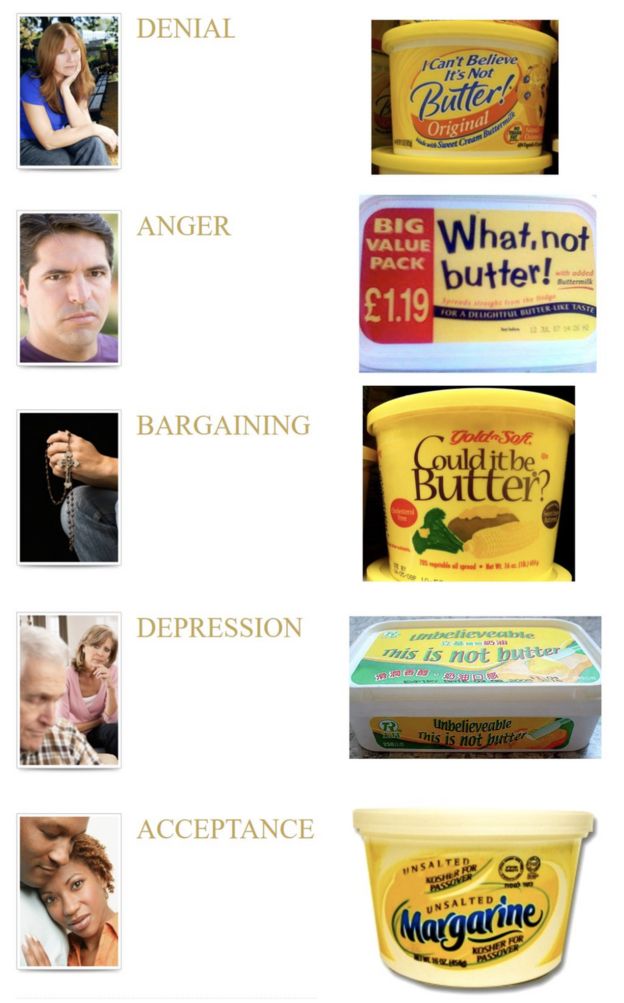

Denial. Anger. Bargaining. Depression. Acceptance. Everyone knows the theory that when we grieve we go through a number of stages – it turns up everywhere from palliative care units to boardrooms. A viral article told us we’d experience them during the coronavirus pandemic. But do we all grieve in the same way?

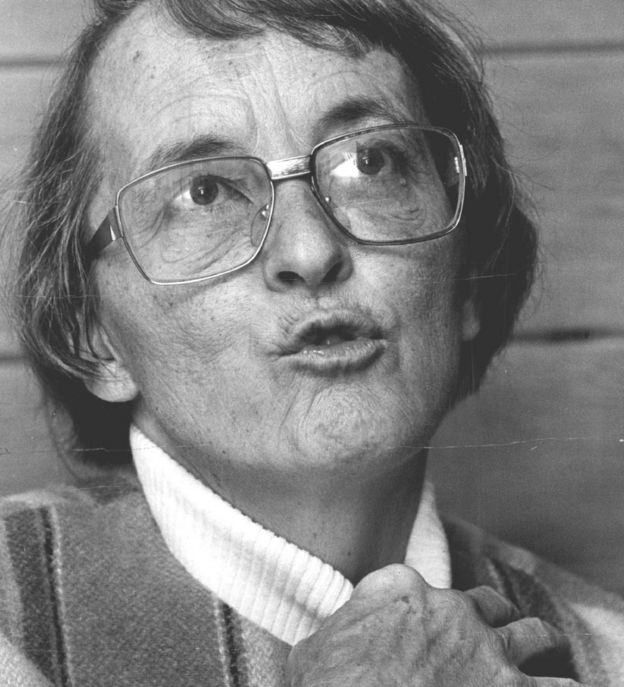

When Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross moved to the US in 1958 she was shocked by the way the hospitals she worked in dealt with dying patients.

“Everything was huge and very depersonalised, very technical,” she told the BBC in a 1983 interview. “Patients who were terminally ill were literally left alone, nobody talked to them.”

So she started running a seminar for medical students at the University of Colorado where she’d interview people who were dying about how they felt about death. Although she met with stiff resistance from her colleagues, there was soon standing room only.

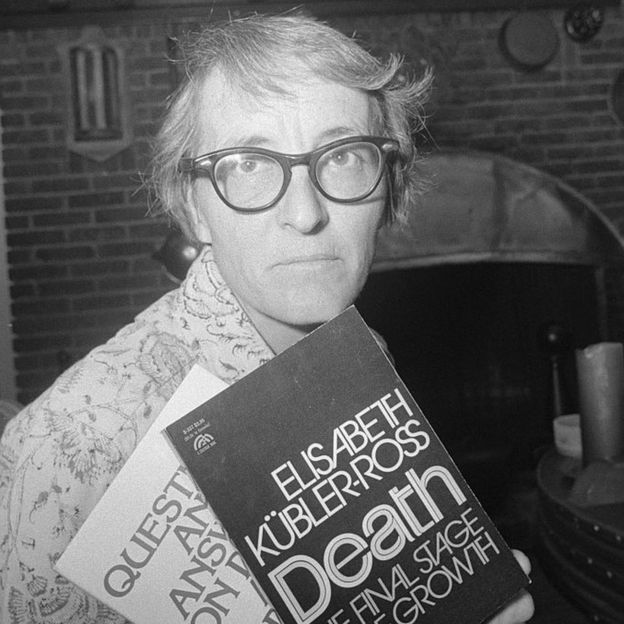

These interviews led in 1969 to a book called On Death and Dying. In it, she began by describing how patients talk about dying, and went on to discuss how end-of-life care could be improved.

The part of it that stuck in the public imagination was the idea that when a person is diagnosed with a terminal illness they go through a series of emotional stages.

Kübler-Ross described five of them in detail:

- denial – “No, not me, it cannot be true”

- anger – “Why me?”

- bargaining – attempting to postpone death with “good behaviour”

- depression – when reacting to their illness, and preparing for their death

- acceptance – “The final rest before the long journey”

She described them as “defence mechanisms… coping mechanisms to deal with extremely difficult situations”.

There were never just five stages, though. While each of these gets a chapter heading, a graphic in the book describes as many 10 or 13 stages, including shock, preparatory grief – and hope.

And her son, Ken Ross, says she wasn’t wedded to the idea that you have to go through them in order.

“The five stages are meant to be a loose framework – they’re not some sort of recipe or a ladder for conquering grief. If people wanted to use different theories or different models, she didn’t care. She just wanted to begin the conversation.”

On Death and Dying became a bestseller, and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was soon deluged with letters from patients and doctors all over the world. “The phone started ringing non-stop,” remembers Ken Ross. “The mailman started coming twice a day.”

The five stages took on a life of their own. They were used to train doctors and therapists, passed on to patients and their families.

They’ve been referenced in TV series from Star Trek to Sesame Street. They’ve been parodied in cartoons, and they’ve also inspired hundreds of musicians and artists.

Thousands of academic papers have been written applying the stages to a huge range of emotional experiences, from athletes dealing with career-ending injuries to Apple consumers responding to the iPhone 5.

They’re also used as a management tool: the Kübler-Ross Change Curve is used by big companies from Boeing to IBM – including the BBC – to help shepherd their employees through periods of change.

And they’re applicable to all of us during the coronavirus pandemic, says grief expert David Kessler. He worked with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and co-authored her last book, On Grief and Grieving, and an interview he gave to the Harvard Business Review at the start of the pandemic went viral, as people sought to understand their emotional responses to the crisis.

“There’s denial, which we saw a lot of early on: This virus won’t affect us. There’s anger: You’re making me stay home and taking away my activities. There’s bargaining: Okay, if I social distance for two weeks everything will be better, right? There’s sadness: I don’t know when this will end. And finally there’s acceptance. This is happening; I have to figure out how to proceed.

“Acceptance, as you might imagine, is where the power lies. We find control in acceptance. I can wash my hands. I can keep a safe distance. I can learn how to work virtually.”

“It’s a roadmap,” says George Bonanno, professor of clinical psychology and head of the Loss, Trauma and Emotion lab at Columbia University.

“When people are hurting, they want to know, ‘How long is this going to last? What will happen to me?’ They want something to hold on to. And the stages model gives them that.”

“They’re seductive,” agrees Charles A Corr, social psychologist and author of Death and Dying, Life and Living. “They offer you an easy way to categorise people who are in those situations, and they happen to fit with five fingers in a hand so you can tick them off.”

But George Bonanno says they can do more harm than good. “People who don’t go through these stages – and as far as I can tell that’s most people – can be led to believe that they are grieving incorrectly,” he argues.

He says he’s seen many examples over the years of people “who were assuming they should feel a certain way, or their friends and relatives were assuming they should feel a certain way, and they weren’t, and people were suggesting maybe they should see a therapist”.

And there’s very little concrete evidence for the existence of five stages of grief. The most extensive longitudinal study on the stages was published in 2007, based on a series of interviews with recently bereaved people. It concluded that although Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s stages were present in different combinations, the most prevalent emotion reported at all stages was acceptance. Denial (or disbelief, as the study termed it) was very low, and the second strongest emotion reported was “yearning”, which was not one of the original five stages. The study has been criticised, though, for selective sampling and overstating its findings.

But does it matter if the stages aren’t backed by empirical research?

David Kessler says that while academics debate, the grieving people he meets in his work still find meaning in the theory.

“I see people who say, ‘I don’t know what’s wrong with me, I think I’m crazy – one moment I’m angry, the next moment I’m sad.’ And I say, ‘There’s a name for a lot of those feelings, those are called the stages of grief,’ and they go: ‘Oh, there’s a stage called anger? Oh I’m in that a lot!’ I think it actually makes people feel more normal.”

“In some ways, if she had never used the word ‘stage’ and said that there were five of them, maybe we would have been better off,” says Charles Corr. “But people might not have paid as much attention to her.”

He says that the idea that there are five fixed stages like a list of medical symptoms distracts from the real lessons to be learnt from Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s work

She wanted to talk more widely about death and dying: helping terminally ill people come to terms with their diagnoses, helping caregivers and family members listen to them and support them while dealing with their own emotions, and encouraging everybody to live their life as fully as possible in the knowledge that their time on Earth is finite.

“Terminally ill people can teach us everything – not just about dying, but about living,” she said in 1983.

Through the 1970s and 1980s, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross travelled the world giving lectures and workshops to thousands of people about death and dying. She was a passionate advocate of the hospice movement pioneered by British nurse Cicely Saunders. She set up hospices all over the world, including the first in the Netherlands. In 1999, Time Magazine named her one of the 100 most important thinkers of the 20th Century.

Her professional reputation began to decline when she expanded her work on end-of-life care into theories about what happens after death, and started researching near-death experiences and spirit mediums.

She became involved with a so-called psychic called Jay Barham, but there was a scandal in 1979 when it was revealed that he had molested female participants during séances, while pretending to be an “afterlife entity”.

In the 1980s she started to set up a hospice in rural Virginia for children dying of Aids, in the face of strong local opposition. In 1995 her farmhouse burnt down in suspicious circumstances and the following day Elisabeth Kübler-Ross had the first of a series of strokes. She moved to be near her son, Ken, in Arizona, where she spent the last nine years of her life.

In her final broadcast interview with Oprah Winfrey she described her feelings about her own death as “just angry, angry, angry”.

“Unfortunately the public didn’t want her to go through her own stages,” says Ken. “They thought the great doctor of death and dying should just be some angelic person who arrives at acceptance from the get-go – but we all have to deal with grief and loss in different ways.”

The Five Stages of Grief are no longer widely taught in medical settings – although the Kübler-Ross Change Curve lives on in executive training and change management, and the stages still inspire some really great memes.

A variety of other theories on how best to process grief have now come to the fore.

David Kessler believes that the key to grief is meaning – a sixth stage which he added to Elisabeth’s list, with the permission of the Kübler-Ross family.

“There’s a million different ways to find meaning. It could be that maybe I’m a better person because of my loved one’s death. It could be that they died in a way they shouldn’t have died so I want to make the world a safer place so no-one has to die in that way.”

Charles Corr recommends a theory called the “dual process model” by Dutch researchers Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut, which suggests that when people grieve they oscillate between processing their loss and preparing for new challenges in life.

George Bonanno, meanwhile, has identified four common trajectories for grief. Many people are relatively resilient and will experience little or no depression, he says, while some will experience chronic grief that takes years to clear, some will experience the return of pre-existing depression, and some people may even find their moods lift following the loss of their loved one.

Most people, he says, will feel better eventually. But he admits that his approach doesn’t provide the same clarity as the theory of stages.

“I can tell someone, ‘You’re probably going to be OK’ – but ‘You’re probably going to be OK’ isn’t nearly as appealing, right?”

Grief is hard to control and distressing – and the idea that there is a roadmap is soothing, even if it’s an illusion.

In Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s last book, On Grief and Grieving, she wrote that her theory of stages was “never meant to help tuck messy emotions into neat packages”.

Grief is different for everyone, even if there are occasionally some similarities. Everyone has to make their own way through.

You may also be interested in:

Few people openly admit to holding racist beliefs but many psychologists claim most of us are nonetheless unintentionally racist. We hold, what are called “implicit biases”. So what is implicit bias, how is it measured and what, if anything, can be done about it?

Or you may be interested in:

Iain Cunningham always believed that his birth had something to do with his mother’s death, but whatever it was seemed to be a family secret that couldn’t be discussed. It wasn’t until Iain was an adult with a family of his own that he uncovered who his mother really was and why she had died.