Gillette adverts stand against toxic masculinity. Budweiser makes specially-decorated cups to encourage non-binary and gender-fluid people to feel pride in their identity.

These examples of so-called “woke capitalism”- of corporations promoting progressive social causes – may feel ostentatiously up-to-the-moment. But woke capitalism is not as new as you might think.

Back in 1850, social progress certainly had further to go.

A couple of years earlier, American campaigner Elizabeth Cady Stanton had caused controversy at a women’s rights convention by calling for women to be given the vote. Even her supporters worried that it was too ambitious.

Meanwhile, in Boston, a failed actor was trying to make his fortune as an inventor.

He had rented space in a workshop showroom, hoping to sell his machine for carving wooden type. But wooden type was falling out of fashion. The device was ingenious, but nobody wanted to buy one.

The workshop owner invited the demoralised inventor to take a look at another product which was also struggling: the sewing machine. It did not work very well. Nobody had succeeded in making one that did, despite many attempts for many decades.

The opportunity was clear. True, the time of a seamstress was not expensive – as the New York Herald said: “We know of no class of workwomen who are more poorly paid for their work or who suffer more privation and hardship.” But sewing took so much time – 14 hours for a single shirt – that there would be a fortune in speeding it up.

And it was not only seamstresses who suffered: most wives and daughters were expected to sew. This “never-ending, ever-beginning” task, in the words of contemporary writer Sarah Hale, made their lives “nothing but a dull round of everlasting toil”.

In that Boston workshop, the inventor sized up the machine he had been asked to admire, and quipped: “You want to do away with the only thing that keeps women quiet.”

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme’s sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

That failed-actor-turned-inventor was Isaac Merritt Singer. He was flamboyant, charismatic, capable of great generosity – but ruthless, too.

He was an incorrigible womaniser who fathered at least 22 children.

For years he managed to run three families, not all of whom were aware the others existed, and all while technically still married to someone else entirely. At least one woman complained that he beat her.

The singer was, in short, not a natural supporter of women’s rights – although his behaviour might have rallied some women to the cause.

His biographer, Ruth Brandon, dryly remarks that he was “the kind of man who adds a certain backbone of solidity to the feminist movement”.

Singer contemplated the prototype sewing machine.

“In place of the shuttle going round in a circle,” he told the workshop owner, “I would have it move to and fro in a straight line, and in place of the needle bar pushing a curved needle horizontally, I would have a straight needle moving up and down.”

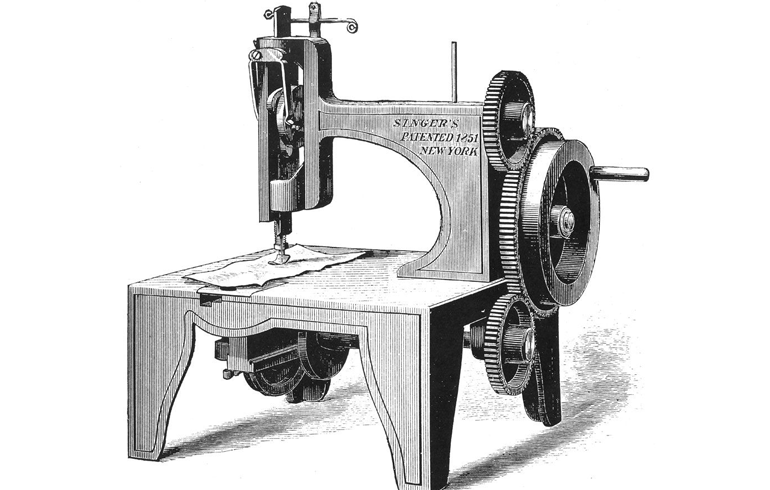

Singer patented his tweaks and started to sell his version of the machine. It was impressive: the first design that really worked. You could make a shirt in just an hour.

Unfortunately, it also relied on various other innovations which had already been patented by other inventors – such as the grooved, eye-pointed needle, to make a lock stitch and the mechanism for feeding the cloth.

During the so-called “sewing machine war” of the 1850s, rival manufacturers seemed to be more interested in suing each other for patent infringement than selling sewing machines.

Finally, a lawyer banged their heads together, pointing out that between them were four lots of people who owned patents to all the elements needed to make a good machine. Why not license each other, and work together to sue everyone else?

Freed from legal distractions, the sewing machine market took off – and Singer came to dominate it. That might have surprised anyone who had seen how his factories compared with those of his rivals.

Others had rushed to embrace what was known as the “American system” of manufacturing, using bespoke tools and interchangeable parts. Yet Singer was late to this party: for years his machines were made from hand-filed parts and store-bought nuts and bolts.

But Singer and his canny business partner, Edward Clark, were pioneers in another way: marketing.

Sewing machines were expensive, costing several months’ income for the average family.

Clark came up with the idea of hire purchase: families could rent the machine for a few dollars a month – and, when their rental payments totalled the purchase price, they would own it.

It helped overcome the bad reputation built up by the slower, less reliable machines of bygone years. So did Singer’s army of agents, who would set up the machine when you bought it, and call back to check it was working.

Still, all these marketing efforts faced a problem. And that problem was misogyny.

For a flavour of the attitudes Stanton was up against, consider two cartoons. One shows a man asking why you would buy a “sewing machine” when you could simply marry one.

In another, a salesman says women will get more time to “improve their intellects!” The absurdity was understood.

Such prejudice fuelled doubts that women could operate these expensive machines.

Singer’s business depended on showing that they could, no matter how little respect he might have shown for the women in his own life.

He rented a shop window on Broadway in New York, and employed young women to demonstrate his machines – they drew quite a crowd.

Singer’s adverts cast women as decision-makers: “Sold only by the maker directly to the women of the family.” They implied that women should aspire to financial independence: “Any good female operator can earn with them $1,000 a year!”

By 1860, the New York Times was gushing: no other invention had brought “so great a relief for our mothers and daughters”. Seamstresses had found “better remuneration and lighter toil”.

Still, the Times rather undercut its gender-conscious credentials by attributing all this to the “inventive genius of man”.

Perhaps we should ask a woman. Here’s Sarah Hale, from Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine in 1860: “The needlewoman is… able to rest at night, and have time through the day for family occupations and enjoyments. Is this not a great gain for the world?”

There are plenty of sceptics about “woke capitalism” today. It is all just a ruse to sell more beer and razors, isn’t it? Perhaps it is. The singer liked to say he cared only for the dimes.

But he is also proof that that social progress can be advanced by the most self-interested of motives.

The author writes the Financial Times’s Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme’s sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Source: BBC