Hong Kong (CNN)Ou Jinzhong has been on the run for more than a week.

Accused of killing two neighbors and injuring three others, the 55-year-old villager in China’s southern Fujian province is wanted by police. The local government has also offered cash rewards for clues to his whereabouts — or proof of his death.

The manhunt has gripped millions of Chinese people — but not because they want to see him arrested. On the contrary, many are openly hoping he is never caught.

“Uncle, run away. Hope you can still find happiness for the remainder of your life,” said a top comment on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like platform.

The outpouring of sympathy and support is highly unusual for an alleged killer in China, where murder is punishable by death.

According to police, Ou is the prime suspect for an attack allegedly committed on October 10. Local police and the Pinghai county government did not offer details about the weapon allegedly used or reveal the identities of the dead and injured.

The victims included four generations of one family living next door to Ou, according to Chinese media. A village official told state-run media Beijing News a 70-year-old man and his daughter-in-law died in the alleged attack. The man’s wife, 30-year-old grandson and 10-year-old great grandson were also injured, it added.

CNN has sought comment from police and county officials but has not received a response.

In the absence of official information, Chinese media and the public used accounts of fellow villagers, Ou’s past Weibo posts, and previous media reports to piece together an unofficial version of events that could have led to the killings.

They claim Ou was an ordinary man pushed to the brink of despair over a years-long housing dispute. Public sympathy surged further after reports emerged that he had saved a young boy from drowning at sea three decades ago and rescued two dolphins that were nearly stranded in 2008.

Many blamed Ou’s apparent transition from savior to murder suspect on the ills that have long plagued China’s local governance, from abuse of power to official inaction. Others see it as a reflection of the broader failure of the country’s legal and bureaucratic system, exacerbated by a besieged free press and a crippled civil society. And some warn that, if things do not change, similar tragedies will happen in the future.

A house that could not be built

For nearly five years, Ou and his family — including his 89-year-old mother — did not have a home, according to Ou’s Weibo posts and Chinese media reports. Instead, they lived in a tiny tin shack in a seaside village in Putian city.

CNN cannot independently verify the authenticity of Ou’s account, though its posts contained detailed personal information, including his national ID and cell phone number. CNN has tried to call the number, but the phone has been switched off.

According to the posts, Ou was repeatedly prevented from building his own house due to land disputes with his neighbor — a deep grievance he had tried in vain to resolve.

It all started in 2017, when Ou decided to demolish his dilapidated house and build a new one, according to his Weibo posts. He said the government approved his application for reconstruction, so he went ahead and tore down the old house. Since then, however, he said he had been unable to build the new one because his neighbor repeatedly blocked construction work.

On Weibo, Ou said he sought help time and again from police, village officials, the government and the media, but the problem remained unresolved. A village official confirmed the land disputes to the Beijing News, saying local cadres had tried to meditate, to no avail.

After years of acrimony, the final straw reportedly came on October 10, when a typhoon tore apart the tin sheet covering Ou’s shack and blew a fragment into the neighbor’s vegetable plot. Ou and the neighbor allegedly got into a dispute when he came over to collect the broken sheet, and the situation quickly escalated, according to China News Week, a state-run news magazine.

Authorities have not revealed the exact details of the alleged murders and it’s not clear if there were any witnesses, or what scene confronted officers when they came to the home.

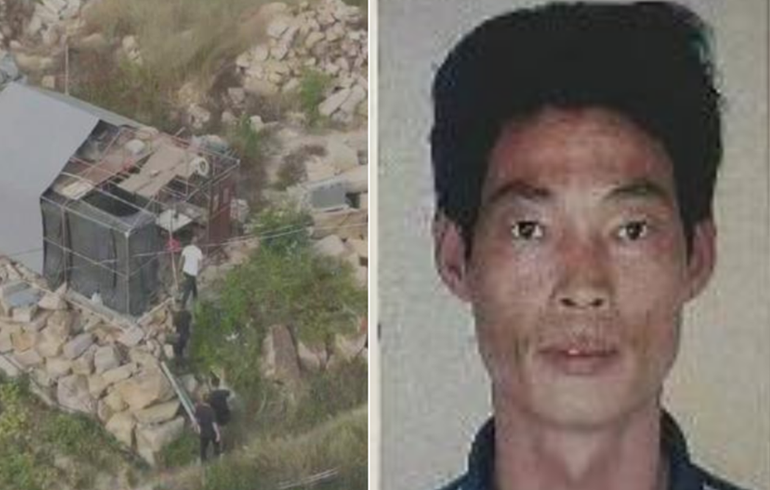

As the news spread, photos of Ou’s shack surfaced online, and many expressed shock at its shabby state. The ripped tin sheet had exposed the shack’s sparse metal skeleton, as well as a layer of black plastic supposedly used to keep out the wind. It stands amid piles of rubble, just a stone’s throw from his neighbor’s four-story house.

That Ou and his octogenarian mother lived in such harsh conditions drew widespread sympathy online. A village official later told Beijing News that Ou built the shack in 2019, and he lived there alone. But it was his failed attempts to seek help that sparked a groundswell of anger.

A relative of the victims has since denied they were bullies, or have political connections, in an interview with a digital news outlet run by a Wuhan newspaper.

Inside his shack, Ou had kept a piece of cigarette packaging paper, on the back of which he wrote dozens of phone numbers — of Communist Party organizations, government departments, state media outlets and various whistleblowing hotlines, according to Beijing News.

“A normal society shouldn’t push a law-abiding citizen to a point of despair, or even drive them to commit crimes. If they exhausted all legal means and still can’t defend their legitimate rights, their private remedy will inevitably arouse widespread sympathy,” a commentator said on Weibo.

Ou’s frustration and despair were detailed on his Weibo account, which he opened earlier this year in an apparent attempt to draw public attention to his case. “Shouldn’t the government protect ordinary people? Why are the rich and powerful so arrogant?” he asked in a post in January, using hashtags of the district and municipal petition bureaus to draw official attention.

“It’s always been the case that honest people play by the rules, but the law will never stand with honest people,” he wrote in another post. “I hope someone can tell me where else I can appeal. I’ve visited both the provincial and municipal bureaus of letters and calls, and received no response at all. Please everybody, I beg you to show me a path forward.”

In May, he posted a screenshot of a WeChat message he sent to a provincial news website, hoping it would report on his case. In another post, he hashtagged the mayor of Putian: “Hello mayor! I’m not very educated. If you can see this, I beg you to help us out, thank you!”

His posts gained minimal attention, with a couple of occasional likes.

Vanished and wanted

The official response and public attention Ou sought never came — until news of the alleged murders broke on October 10.

In the days since, Ou’s case has made headlines and dominated social media discussions. Hundreds of search crew members are looking for him in nearby hills, where he was last seen.

In a video captured by a roadside security camera on October 10, Ou took long, heavy strides, his shoulders hunched over, his right hand tugging at a corner of his white T-shirt before his lanky figure disappeared behind a boulder.

Then, on October 12, his Weibo account vanished too, after his posts went viral and sparked a public outcry. The district government issued a statement that night, vowing to investigate allegations of inaction by local officials.

On Weibo, a hashtag of Ou’s user name continued to gain traction, drawing more than 7 million views — but by October 13, that hashtag had disappeared, too.

The censorship further fueled public anger. Many blamed local authorities for failing to address Ou’s concerns.

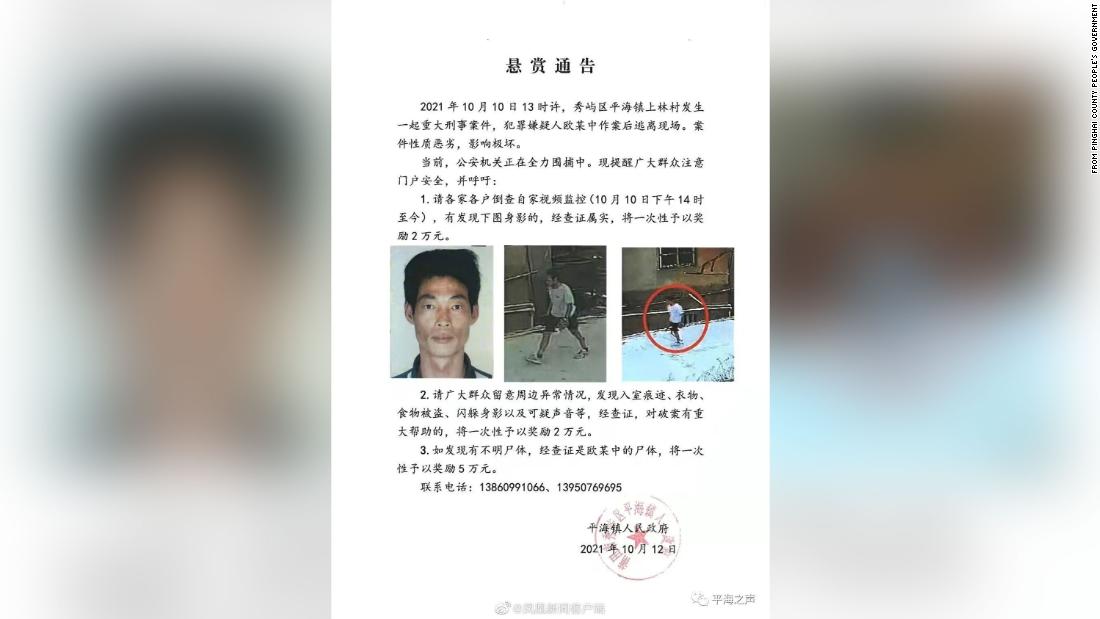

On October 13, the local government of Pinghai county issued a bounty for Ou on social media app Wechat: 20,000 yuan ($3,106) for any security footage or information leading to his arrest or 50,000 yuan ($7,765) for proof of his dead body.

The notice drew immediate backlash. “The cash reward for discovering a body is higher than that for a living man — is this really a government notice?” asked a top comment with 60,000 likes. “It’s because a dead person can no longer speak,” said the top reply.

The bounty notice was later deleted from the government’s WeChat account.

‘You can’t be in hiding forever’

Liu Xiaoyuan, a veteran human rights lawyer, said the sympathy for Ou was unsurprising.

“The public is keenly aware that he had allegedly resorted to violence — they’re not in support of him conducting murder. Instead, they are angry about the failure of relevant authorities to respond to Ou’s appeal for help and carry out their duties,” he said.

Land disputes are common in rural China, according to Liu, who has helped many farmers defend their rights during his decades-long career.

“This is a heavy lesson for local governments: if they don’t pay attention to the disputes and grievances of the people, conflicts could easily escalate,” he said. “In Ou’s case, if any government department had stepped in to help him resolve the dispute, he might not have ended up on the path of murder.”

“If any government department had stepped in to help him resolve the dispute, he might not have ended up on the path of murder.”

Liu Xiaoyuan, lawyer

As the manhunt continues, some have urged Ou to turn himself in, including the man who claimed he was rescued by Ou from the sea as a boy three decades ago.

“It really pains me to see this happen,” he said in a video he posted on social media, referring to the alleged murders.

“In my impression, he was a kindhearted and honest man. I hope he can come back and turn himself in. It’s not easy to survive in the mountains. You can’t be in hiding forever.”

Source: CNN