Boeing’s 737 Max plane is safe to return to service in Europe, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (Easa) has said.

It lifts a 22-month flight ban for the jet, which followed two crashes which caused 346 deaths.

The plane has already been cleared to resume flights in the US and Brazil.

This week a senior manager at Boeing’s 737 plant in Seattle warned that recertification had happened too quickly.

But regulators in the US and Europe insist their reviews have been thorough, and that the 737 Max aircraft is now safe.

Easa executive director Patrick Ky said: “We have every confidence that the aircraft is safe, which is the precondition for giving our approval.

“But we will continue to monitor 737 Max operations closely as the aircraft resumes service.

“In parallel, and at our insistence, Boeing has also committed to work to enhance the aircraft still further in the medium term, in order to reach an even higher level of safety.”

Easa represents 31 mainly EU nations, excluding the UK which formally left the bloc this month.

The UK’s Civil Aviation Authority is expected to announce whether it will clear the plane to fly imminently.

Software issues

The 737 Max’s first accident occurred in October 2018, when a Lion Air jet came down in the sea off Indonesia.

The second involved an Ethiopian Airlines version that crashed shortly after takeoff from Addis Ababa, just four months later.

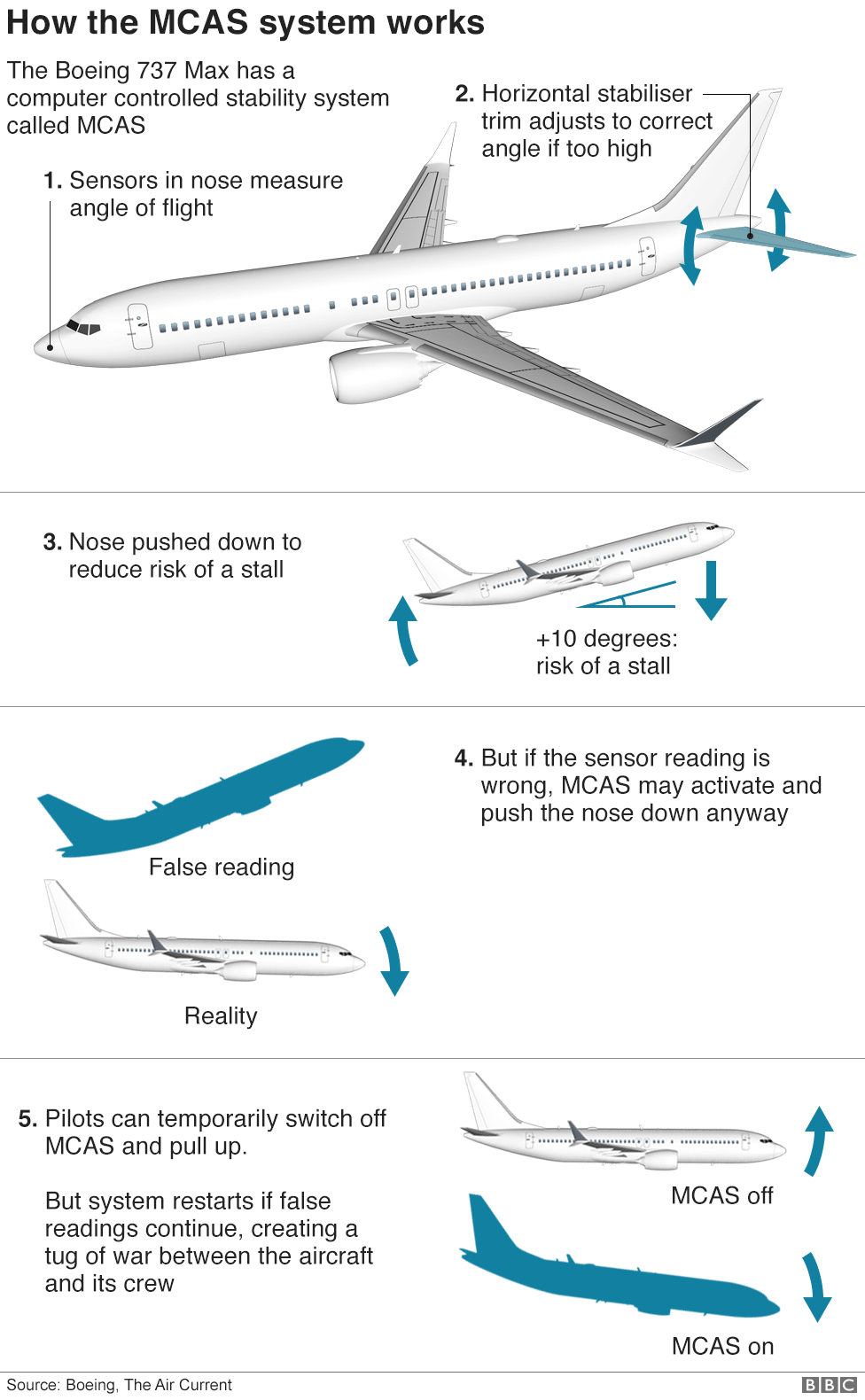

Both have been attributed to flawed flight control software, which became active at the wrong time and prompted the aircraft to go into a catastrophic dive.

Mr Ky said Easa had done a full investigation independent of Boeing or the US Federal Aviation Administration and “without any economic or political pressure”.

As a result, Easa demanded software upgrades, electrical working rework, maintenance checks, operations manual updates and crew training.

“We asked difficult questions until we got answers and pushed for solutions which satisfied our exacting safety requirements,” Mr Ky said.

It comes days after a report by former Boeing manager Ed Pierson, which claims that regulators and investigators have largely ignored factors, which he believes, may have played a direct role in the accidents.

He said that further investigation of electrical issues and production quality problems at the 737 factory is badly needed.

Celebrated aviation safety campaigner Captain Chesley Sullenberger – one of the pilots who safely landed an engineless Airbus plane in the Hudson river in New York in 2009 – also believes that modifications to the Max do not go far enough.

He says changes are needed to warning systems aboard the plane, which were carried over from a previous version of the 737 and are “not up to modern standards”.

Boeing has already agreed to pay $2.5bn (£1.8bn) to settle US criminal charges that it hid information from safety officials about the design of the planes.

The US Justice Department said the firm chose “profit over candour”, impeding oversight of the planes.

About $500m of that will go to families of the people killed in the tragedies.

However, attorneys for the victims of the Ethiopian Airlines crash have said the deal would not end their pending civil lawsuit against Boeing.

On Wednesday, Boeing posted a record $12bn annual loss after it delayed its all-new 777X jet for the third time, incurring huge charges.

The coronavirus crisis has caused demand for the industry’s largest jetliners to fall, with airline customers shunning deliveries of planes due international travel restrictions.

The 737 Max has already been cleared to fly in North America and Brazil – now it has the go-ahead from European regulators as well.

It’s a major step for Boeing – although with the current travel restrictions in place, it’s likely to be a while before the decision has much practical effect.

But the controversy won’t end there. Relatives of those who died in the Ethiopian Airlines accident have made it clear they haven’t heard enough to be sure the aircraft – modified in accordance with regulators’ wishes – is truly safe.

And this week, a former senior manager at the 737 factory told the BBC why he thought existing planes might still be carrying potentially dangerous manufacturing defects.

That may explain why Easa has also chosen to publish a report setting out the detailed reasoning behind its decision.

Ultimately, the 737 Max may we’ll have decades of successful service ahead of it. But for the moment, winning back passenger confidence will be a formidable challenge.

Source: BBC