In the space of a month, the United Kingdom has transformed beyond recognition. And most of us haven’t had time to stop and take stock.

One Friday afternoon, when the UK was another country, a chalkboard leaned against the outside wall of a country pub. A message had been written in neat, thin capital letters.

“Unfortunately a customer who visited us has tested positive for the coronavirus,” it read. “So as a precautionary measure we are closing for a full deep clean.” It was signed by the landlord and landlady, who apologised for the inconvenience.

The pub was located along a quiet, narrow road just outside Haslemere in Surrey. The patient who had gone there lived somewhere in the county. Unlike previous British cases detected up to that point – he was the 20th – he hadn’t been abroad recently. As far as anyone knew, he was the first to catch the virus inside the UK.

On the same day, 28 February 2020, came another news update. A grimmer milestone. A British man who’d been infected on the Diamond Princess cruise ship became the first UK citizen to die, in Japan, from Covid-19.

That afternoon, children were still in classrooms and adults were still at work. People shook hands and hugged and kissed. In the evening, they went to pubs and restaurants. Some went on dates and others visited elderly relatives. They assembled in groups and mingled with residents of other households.

As the weekend went on, football fans crammed into stadiums. Worshippers gathered in churches, mosques, temples and synagogues.

You could go outside for as long as you liked, if you didn’t mind the rain. On supermarket shelves, toilet paper and paracetamol were plentiful. Recent storms had left large swathes of the country flooded, but for most British people, life went on as it always had and seemingly always would.

Insofar as any of this describes a British way of life, though, it was one that ceased to exist entirely within just a few weeks.

The changes didn’t happen smoothly, in steady, barely noticeable steps. Instead, the UK’s sense of what was normal shifted in sudden movements, as though a ratchet was being yanked.

On 28 February 2020 people in the UK were already taking notice of the outbreak. It would have been difficult to ignore entirely the headlines about what was happening in China, South Korea, Iran and Italy. The first confirmed cases among travellers returning to the UK had come as early as January, but it still seemed possible to regard this as something happening, for the most part, a long way away.

Not every newspaper front page that Friday morning led with Covid-19 – the Daily Mail splashed on the saga of Harry and Meghan, the Daily Express with Brexit talks – but most did. In the final week of the month 442,675 phone calls were made to the non-emergency NHS line 111. People weren’t yet panicking, but a generalised sense of low-level anxiety was everywhere.

By 1 March, the virus had reached the four corners of the United Kingdom – cases had been detected in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Two days later, with the total number at 51, Prime Minister Boris Johnson stood behind a lectern and launched the government’s Coronavirus Action Plan. The outbreak was declared a “level four incident”.

Up to a fifth of the workforce might be off sick at its peak, the prime minister warned. Schools might have to close and large-scale gatherings be reduced. However seriously anyone took the warning, it was still difficult to visualise.

The following day, a woman in her 70s with an underlying condition – those last four words soon became grimly familiar to anyone who followed news bulletins – became the first person to die inside the UK after testing positive for the virus. The first reports of hand sanitiser selling out in supermarkets were published.

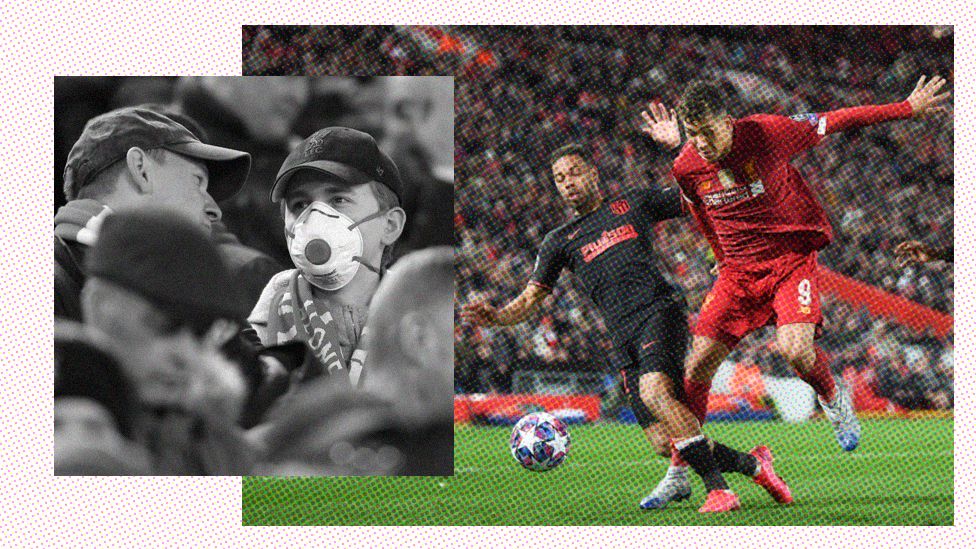

Each day the number of confirmed cases crept up – 115 by 5 March, 206 by 7 March, 273 by 8 March. On 11 March, the day that the World Health Organization declared a pandemic, Liverpool FC hosted Atletico Madrid – who were already playing their home games behind closed doors.

There were anxieties about whether it was a great idea to allow the 3,000 Spanish supporters to fly into a major British city where they would eat, drink, mingle and sleep. Anyone with plans to fly out of the UK was beginning to reconsider.

Another twist of the ratchet was imminent.

The following day, the government’s Sage committee of scientific experts was shown revised modelling of the likely death toll. The figures, according to the Sunday Times, were “shattering”. If nothing was done, there would be 510,000 deaths. Under the existing “mitigation” strategy – to shield the most vulnerable while letting everyone go about their business mostly as normal – there would be a quarter of a million.

In a press conference, the prime minister told anyone with a continuous cough or a fever to self-isolate. His instruction came with a warning that “many more families are going to lose loved ones before their time”. The bluntness was shocking. Some asked why, in that case, more wasn’t being done.

On Friday 13, the London Marathon, the Premier League and English Football League and May’s local elections were all postponed. Scotland had its first coronavirus-related death.

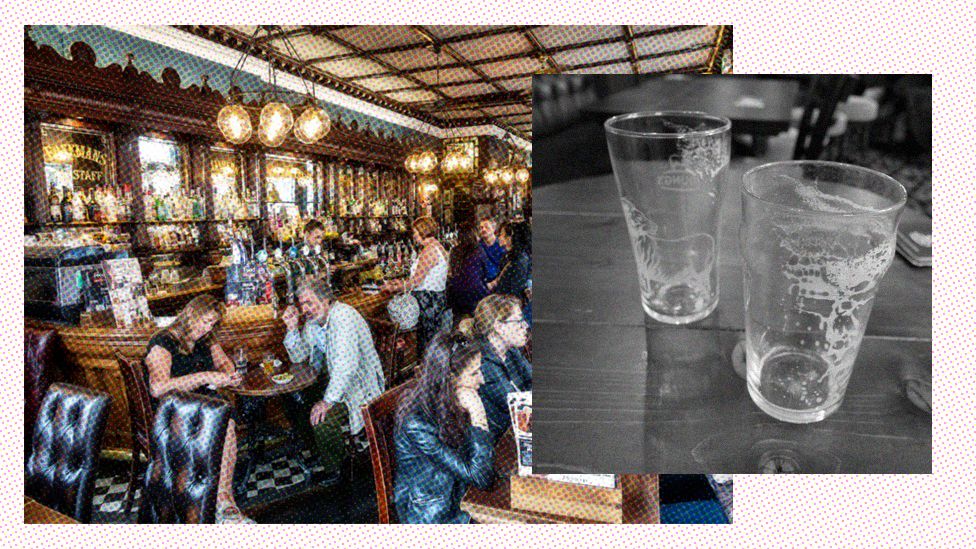

Saturday 14 and Sunday 15 March was the last relatively normal weekend. You couldn’t watch league football but you could go to the pub. Hand sanitiser now wasn’t to be found on any supermarket shelves, but you could tell your friends about your plans to practise “social distancing” if you met them on the street.

Around the country, people looked at Italy, France and Spain, which had already gone into lockdown, and wondered if the UK was next. Volunteers began forming mutual aid groups to deliver food and medicine to vulnerable people who were self-isolating.

In person and on WhatsApp, families and groups of friends argued about what it all meant. The more anxious wondered why the British government was moving more cautiously than its counterparts on the continent. The more blasé complained about why they were going to all this bother. Wasn’t it just a bit of flu?

The latter sentiment was exactly the kind of thing the government’s advisers were most worried about. On Monday 16, the prime minister advised against “non-essential” travel, urged people to avoid pubs and clubs and work from home.

Across the country, kitchen tables were cleared to make way for laptops. Thanks to Skype and the virtual meetings app, Zoom, white-collar workers started getting a glimpse of their colleagues’ interior decor. Those who couldn’t do their jobs like this wondered how on Earth they were supposed to earn money and stay safe.

On 17 March, the government began holding daily press conferences – events that would soon become regular viewing for nervous families. Just six days after presenting his budget, the Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, announced £300bn in loan guarantees – a huge expansion of state intervention in the economy by a Conservative government.

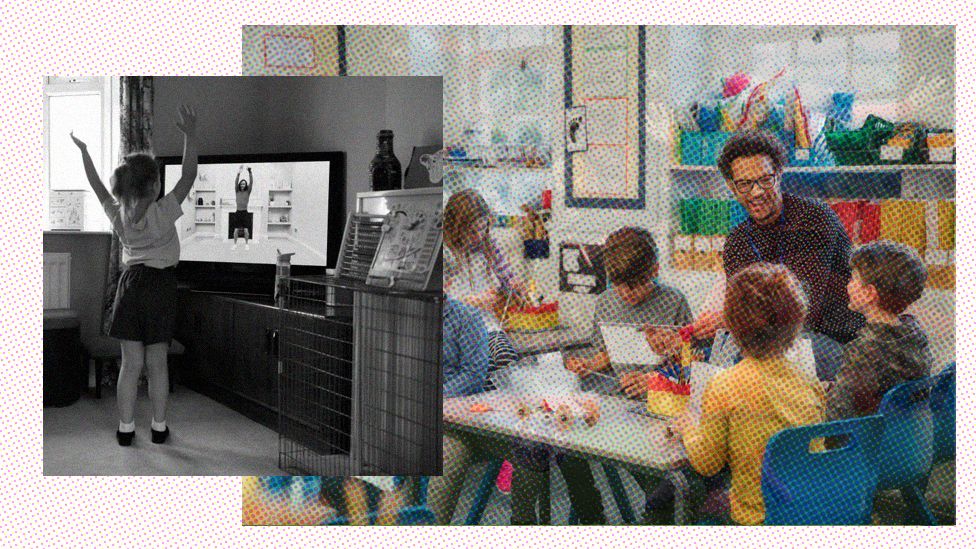

There were still calls for more to be done to stop Britons infecting each other. The following day, most school pupils – those whose parents weren’t designated key workers – were told they wouldn’t go back to their classes until further notice. Exams, proms, farewells to classmates and teachers would now never happen.

But although the UK had been told not to go to restaurants, cafes and pubs, many restaurants, cafes and pubs stayed open. They were quieter than usual but some customers still came. On the evening of Friday 20, the prime minister – who in a long career as a newspaper columnist had steadfastly demonstrated libertarian instincts – ordered restaurants, cafes and pubs to close, a measure that even in the darkest moments of World War Two would have been unthinkable.

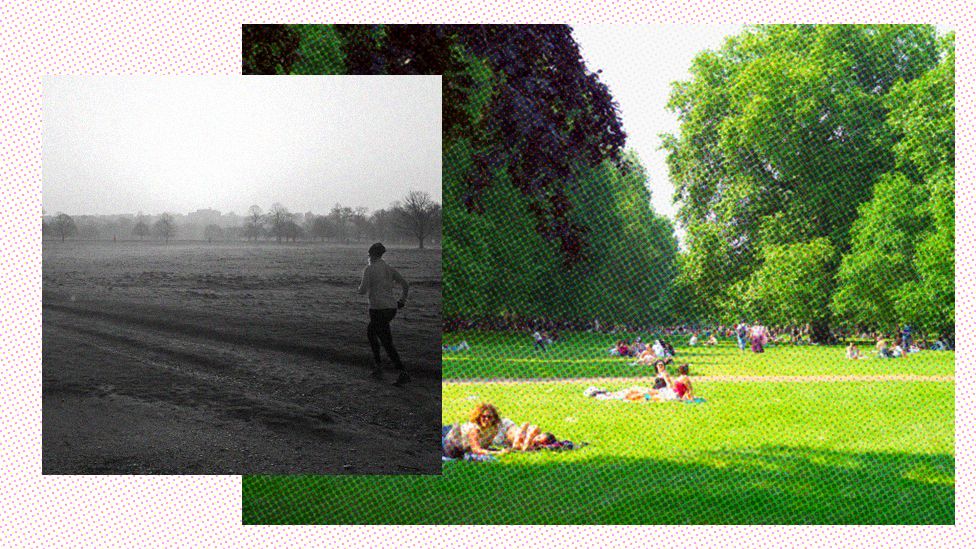

For much of the weekend that followed, there was bright sunshine, and people poured outside to take advantage of the last leisure option open to them. But when they crowded into parks and on to the summit of Snowdon they were seen – and widely condemned. This was not how “social distancing” – now regarded as everyone’s social duty – was meant to operate.

The lockdown was coming.

On Monday 23 at 20:30, the television screens showed the prime minister sitting behind a desk. He was about to announce some of the most draconian restrictions on individual liberty the UK had ever seen.

You could only leave home to exercise once a day, travel to and from work when absolutely necessary and only go shopping for essential items. You had to stand two metres apart from people you didn’t live with. You weren’t to gather in public in groups bigger than two.

The British people were being told to avoid human contact when they needed it most.

All through the following week, people would look forward to their one state-sanctioned form of outdoor exercise a day. Or they would stand in front of their laptops, following the instructions set by the fitness coach, Joe Wicks.

By the time the weekend arrived, there were more than 537,000 confirmed cases in 175 countries. More than a quarter of all the people on the planet were living under some kind of restrictions in their social contact and movements.

British life had been transformed so dramatically, and so fast, that you hadn’t had time to dwell on it. On 28 February, London’s Excel Centre had been hosting The Baby Show, “the UK’s largest parenting event”. A month later, the venue was a giant field hospital.

This wasn’t normal.

Everything was described as “unprecedented” now, because it was. Speaking to the BBC’s The World At One, historian Lord Peter Hennessy predicted that, in future, post-war Britain will be demarcated “BC and AC – before corona and after corona”.

Before 28 February, the UK was still widely portrayed as a place divided by Brexit, with younger, metropolitan Britons on one side, and their older counterparts in towns and the countryside on the other. That soon came to seem an anachronism. Elderly people were most at risk and those of working age, in the NHS and other key professions, were there to try and save them. Everyone was in this together.

The framing of political debate since 2016 seemed inadequate to the new reality. Coronavirus would not be defeated by a populist attack on the elites. More than ever, the UK needed experts to lead the way. But the experts needed the masses, too – if the vast majority of the population didn’t act, then Covid-19 couldn’t be stopped.

Initially, the lockdown was supposed to last three weeks. But a month on from 28 February, the UK is settling in for the long haul, with the prime minister, the health secretary and the first in line to the throne all having tested positive for the virus.

You remember your last trip to the gym, the last drink you had in a cafe or a pub, the last time you hugged your mum or your grandad. You think about the life you once took for granted. You wonder if it will ever return.

Source: BBC