A World Health Organization (WHO) team have come out of quarantine and will start on-the-ground investigations into the origins of the coronavirus in the Chinese city of Wuhan.

The scientists will begin interviewing people from research institutes, hospitals and the seafood market linked to the initial outbreak.

Their research will rely upon evidence provided by Chinese officials.

This comes after months of negotiations between the WHO and Beijing.

The group of 13 experts had arrived in Wuhan on 14 January, and spent two weeks in quarantine that ended on Thursday. While in isolation, the team had been in video calls with each other and Chinese scientists.

On Thursday afternoon they exited their hotel and boarded a bus without speaking to journalists. Earlier in the day members of the team tweeted about the end of their quarantine, including pictures of themselves receiving letters certifying they had completed medical isolation.

“New phase, new priorities,” tweeted Dutch virologist Marion Koopmans.

Before their arrival, the WHO had said its investigators were denied entry into China after one member of the team was turned back and another got stuck in transit. Beijing later said it was a misunderstanding.

Covid-19 was first detected in Wuhan in late 2019, but China has been saying for months that it is not necessarily the place where the virus originated from.

State media has recently suggested the pandemic might have begun outside of China – Spain, Italy or even the US – and have also carried claims that the virus has been entering the country through frozen food imports, though experts have cast doubt on this.

In an earlier interview with the BBC, Professor Dale Fisher, chair of the global outbreak and response unit at the WHO, said he hoped the world would consider the investigation in Wuhan a scientific visit. “It’s not about politics or blame but getting to the bottom of a scientific question,” he said.

Prof Fisher added that most scientists believed that the virus was a “natural event”.

It was initially believed the virus originated in a market in Wuhan selling exotic animals for meat. It was suggested that this was where the virus made the leap from animals to humans.

Looking for answers

Meanwhile a year on since the outbreak began in Wuhan several families of Covid-19 victims are still looking for answers, and some are publicly asking to meet with the WHO team.

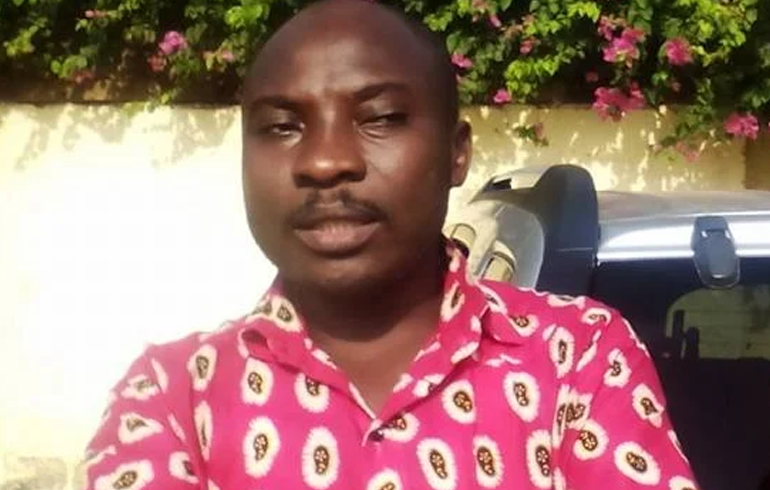

“I think it’s necessary that the experts meet me and other people who have lost family members to the virus, and hear from our experiences. This can only aid their investigation,” said Zhang Hai, a Wuhan native whose father died last February in the city at the start of the outbreak.

“I hope the WHO will not be used as a tool to spread lies,” the 51-year-old told the BBC.

Mr Zhang said he believes delayed reporting about the virus by Wuhan city officials in the initial days of the outbreak cost his father his life.

His family had travelled to the city in January last year from the city of Shenzhen, where they currently live, so that Mr Zhang’s father could receive subsidised surgery for a leg fracture.

The surgery was successful, but Mr Zhang’s father then contracted Covid-19 and subsequently died.

“If it was made known that there was a virus outbreak in the city, we wouldn’t have gone there,” he said.

“By covering up that fact at the time, many lives were lost, so the Wuhan government has knowingly committed murder. They need to be held accountable for that.

Until I get an official apology from the local authorities over what happened to my father, I will not give up.”

Local government officials in Wuhan and its surrounding Hubei province have been accused of downplaying the virus in the early days of the pandemic, and several were fired last year.

Mr Zhang claimed Chinese authorities have blocked his online calls for accountability as well as efforts to organise other families of Covid victims.

He said a WeChat group formed by the families that had at least 80 members was deleted recently without explanation. Six separate accounts which Mr Zhang had set up on microblogging platform Weibo to share his story have also been blocked. “Every time I write something, it’ll just get blocked,” he told the BBC.

Mr Zhang said police have paid visits to his home in Shenzhen as well, and in November last year he was summoned to a police station for questioning.

But he remains unafraid about potential repercussions. “I know I have done nothing wrong,” he said.

Source: BBC