The BBC’s Andrew Harding visits a township in South Africa’s coastal city of Cape Town to see how it has been hit by coronavirus.

While the surfers are back out in large numbers on the waves in False Bay, taking advantage of an easing of some lockdown rules in South Africa, just inland on the sandy, windswept plains of Khayelitsha, coronavirus is spreading fast through the impoverished, crime-ridden township and, in the process, highlighting some of the challenges this whole country is likely to face in the coming weeks.

“Yes, we’re definitely seeing very big numbers currently here,” said Dr Ayanda Trevor Mnguni, head of internal medicine at the 300-bed Khayelitsha District Hospital.

When the health workers need treatment

In a health service already wrestling with a historic shortage of nurses, Dr Mnguni has already had to triple the number of medical staff, and turn the entire hospital into a Covid-19 ward.

But now many of his key workers are, themselves, succumbing to the virus.

“We’ve got a lot of staff who are infected. We’ve had a week where we lost our porters. The following week it was our radiographer. A week after that… our staff from the laboratory,” said Dr Mnguni.

The strains have exposed the underlying health issues in the community.

“The majority of our nurses are themselves patients who’ve got diabetes and hypertension, so that puts a huge strain on the system. Also, we’re noticing an explosion of undiagnosed diabetics, who are now being diagnosed as a result of Covid. And that obviously overwhelms our emergency unit,” added Dr Mnguni.

‘Spreading like wildfire’

With its own wards full, Khayelitsha District Hospital is sending new cases across the road to a new facility, built, in the space of one month, in a sports hall, and run by Médecins Sans Frontières – an organisation that has been a familiar presence in the neighbourhood for 20 years, focusing on the battle against HIV/Aids.South Africa Covid-19 crisis

- Confirmed cases: 159,333

- Total deaths:2,749

- Most deaths:aged 60-69 (717); 50-59 (652); 40-49 (339); 80-89 (246)

- Male deaths:1,444

- Female deaths:1,301

- Worst-affected area:Western Cape (64,377 cases and 1,896 deaths)

Source: South African government (1 July)

The MSF clinic is one of many steps that this province – the Western Cape – has taken to prepare for an anticipated surge of cases.

“Already this is spreading like wildfire,” said Eric Goemaere, a Belgian MSF Doctor who has spent many years in Khayelitsha.

“We are having to take some tough decisions. There’s no point sending the extremely sick cases back to the referral hospital because they don’t have the staff or the equipment. The hospitals in this region cannot cope,” he said.

Instead, the most severe cases are left, almost certainly to die, in a palliative care section in the corner of the sports hall, while the precious supplies of oxygen are reserved for those perceived to have a better chance of recovery.

Everyone volunteering to help

Dr Goemaere, who has long experience fighting TB, HIV and Ebola, emphasised the importance of a community health approach – outsourcing as much work as possible in order to reduce pressure on hospitals.I worry about the old people. There’s nobody to look after them” Theodora Luthuli

Nursery school principal

He also stressed the need to secure reliable supplies of oxygen – one patient can easily use four huge bottles a day – and to find enough staff, particularly nurses, in order to help turn the patients over at regular intervals to lie on their chests.

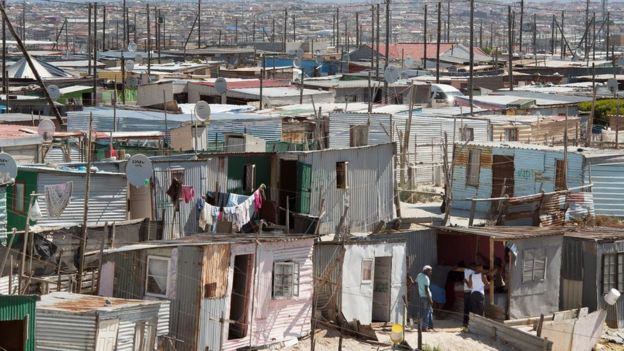

Khayelitsha has so far recorded more than 6,500 cases of coronavirus, the second-highest number in a Cape Town district. The township has a population of about 400,000, according to the 2011 census.

A few miles away, in the neighbouring township of Nyanga East, several hundred people were lining up for a free meal, served by a local nursery school and funded by donations. The elderly stood in their own, separate queue, while children and adults stood in line on either side of the street.

“I’m hungry. No food at home. No money,” said one elderly woman.

The principal of Khanyisa Nursery, Theodora Luthuli, said food aid was being given to 500 to 1,000 people, and the number was rising daily.

“This virus has exposed underlying issues. People were already unemployed here, lockdown or not,” she said.

“I worry about these old people. There’s nobody to look after them, and even the places where they can isolate are becoming full of infection.

“But during this period, we’ve experienced everyone trying to help. A lot of my volunteers are actually men, who are often abusers and cause violence against women. So now they’re saying enough is enough,” said Ms Luthuli.

The survivor

Back in Khayelitsha, 46-year-old Lusanda Jonas was busy exercising in her front yard, shuffling a few steps in her fluffy pink slippers and dressing gown before stopping and rotating her arms in a slow circle.

She had been discharged from hospital a day earlier, having recovered from Covid-19 after spending a fortnight in intensive care.

“People are not taking it seriously. It makes me feel so bad,” said Ms Jonas, a diabetic who works as an administrative secretary at a nearby police station.

She had come home to learn that six people “on this same street” had died from the virus.

“This virus is going to kill more people. You need to stay at home and take care of yourself. You need to wear a mask,” she said, before going inside for a rest.

At a nearby shopping centre, almost everyone was wearing a face mask, and standing patiently in long queues outside banks and supermarkets.

But many people in Khayelitsha live in informal settlements – in home-made tin shacks – where self-isolation and social distancing are near impossibilities.

Another issue being confronted here, alongside a lack of education about the virus, is stigma – a familiar challenge from the long struggle against HIV/Aids.

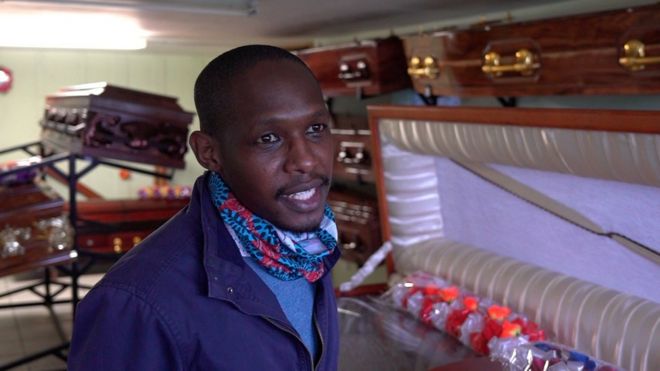

“There’s a whole stigma attached to the fact that someone passed away from Covid,” said Luthando Gqamana, manager of Nothemba Funeral Services – one of the largest in the township. Its motto is “The last people to let you down.”

No funeral rituals

Late one afternoon workers were busy unloading the day’s last three Covid-19 corpses from an undertaker’s van, and moving the body bags into the company’s large freezer unit in a dank warehouse near the railway lines.

Standing beside a display of wooden coffins, Mr Gqamana described how many clients were reluctant to admit that their relatives had died of the virus, and how they became angry when they were told that – since the cause of death was always clearly indicated in official documents – they could not perform certain traditional rituals, like touching or dressing the body of a dead relative.

“When they are burying a loved one and can’t perform certain rituals – that’s when it kicks in that, no, this is actually real,” he said.