Ethiopia is poised to hold what its prime minister calls the nation’s first attempt at free and fair elections, but it is taking place amid deepening insecurity, a boycott by some leading opposition parties, and the Tigray region being consumed not only by conflict but by starvation and the rising threat of famine, writes BBC Africa correspondent Andrew Harding.

This was supposed to be a defining moment for Ethiopia – an ambitious nation eager to reveal itself not simply as Africa’s rising economic powerhouse, but as a fast maturing democracy, finally making a decisive break from decades of authoritarianism and overtly rigged elections.

So, can Ethiopia pull it off? And might this election prove to be a “pivot” point for the conflict in Tigray, as the central government faces growing international pressure for a ceasefire?

It was back in 2018 that Ethiopia gave the clearest sign of its democratic intent in these elections, by inviting a former political prisoner, Birtukan Mideksa, to return from exile to chair the country’s overhauled electoral commission.

Exhilarating transition

How could anyone dispute this giant country’s determination to break with the past and hold free and fair elections, and, by extension, to cement Ethiopia’s dominant position in the region and beyond?

“We are in very good shape,” Ms Birtukan declared recently, of the commission’s lengthy preparations.

Her return reinforced the sense of a nation in the midst of an exhilarating transition – as political prisoners were freed from Ethiopia’s “gulag archipelago,” the media was unmuzzled, and a peace deal signed to end a long border conflict with neighbouring Eritrea.

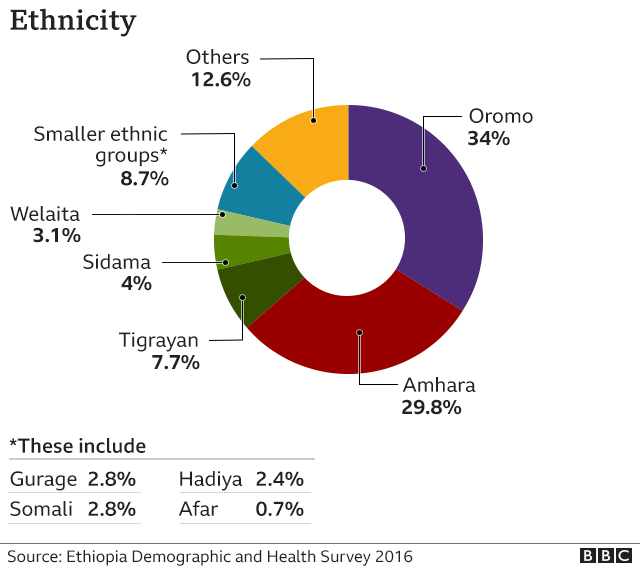

Ethiopia’s young Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019, in part as recognition of his achievements, but also as a spur to further reforms in a country which – as many observers pointed out – would need delicate handling in order to prevent it fracturing into turmoil along ethnic lines.

That turbulence is not quite comparable to the break-up of the Soviet Union. But some of the same historic tensions and risks – of a once-ruthless Marxist state attempting to liberalise while still controlling potentially explosive internal tensions – were clear to many.

Two years later, and is it possible to argue that Mr Abiy’s ambitious reform agenda remains on track?

There seems to be little doubt that Mr Abiy and his new Prosperity Party – formed from the once-mighty ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) – will win a decisive victory at these elections, enabling him to claim a powerful mandate for his policy of “medemer,” or “coming together”.

Under that slogan, Mr Abiy appears keen to nudge Ethiopia away from the ethnic federalism of the EPRDF, and towards a more centralised state.

That likely victory will, almost certainly, be accompanied by rhetoric that looks to put Ethiopia’s current electoral challenges in perspective.

Warnings of famine

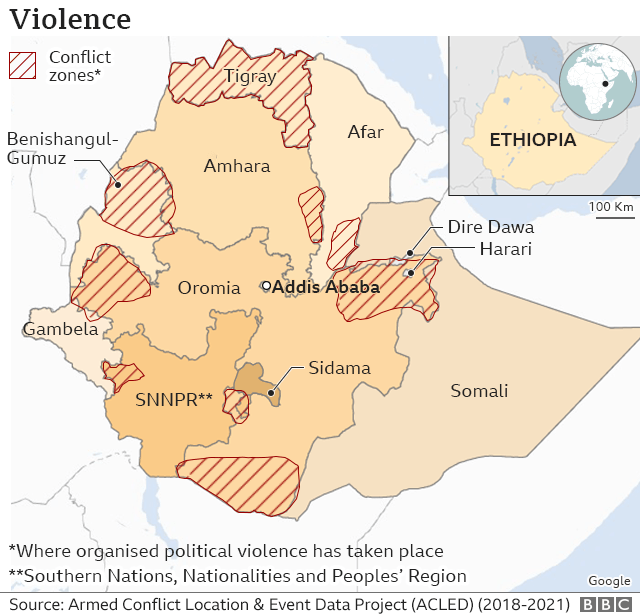

The government will argue that the failure to hold elections in war-torn Tigray is unfortunate but not debilitating, given that the region has only a small fraction of seats in parliament. Tigray can hold elections when the situation there has been stabilised.

International warnings about famine, the government insists, are simply wrong. Besides, it is reasonable to argue that the central government had to act aggressively against a rebellious Tigray in order to prevent larger regions from following suit.

There are major security challenges across much of Ethiopia – in Afar, the Somali region, Amhara, Oromia, Harari, Benishangul-Gumuz, South Wollo and elsewhere. Nearly two million people have been displaced by conflict outside Tigray.

The instability will affect registration, turnout, and the participation of some major opposition parties.

But again, the government and its supporters will argue, this election needs to be seen in proper context – as part of a broader, imperfect process of reform in a nascent democracy, with more than 50 parties already involved.

The answer to violence and incitement by politicians is, surely, not to retreat, or to pretend the elections were flawless, but rather to push ahead with the process in order to keep Ethiopia on a trajectory of reform.

Convinced? Increasingly, many Ethiopians, and foreign observers, are not.

The first concern is about insecurity. Just as Tigray’s decision to push ahead with regional elections last year during the pandemic – a move considered illegal by the central government – helped to steer its then ruling party, the TPLF, towards open conflict, and war, with the Ethiopian state, so there are concerns that holding national elections today, in the midst of so many regional conflicts, will trap Ethiopian politics in a long-term crisis of legitimacy.

That, in turn, could drive new recruits and more support towards the ethnic forces and separatist groups that have already turned their backs on the electoral process in order to challenge Mr Abiy’s centralising impulses.

By that analysis, the price of impatiently pushing ahead with a flawed election next week could be years, or even decades, of escalating conflict.

Then comes the risk that prolonged chaos and conflict – in Tigray and beyond – will drive the Ethiopian state back towards greater authoritarianism.

There’s already evidence of this – not least the number of “political” arrests, and the chilling effect of so many reports of atrocities by government and allied forces in Tigray.

West accused of condescension

Again, it’s worth remembering Russia’s experience of post-Soviet transformation, with the giddy reforms unleashed by Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin soon giving way to a return to repression under Vladimir Putin.

More about Ethiopia’s elections:

How serious are these risks?

The Western nations that once cheered on Ethiopia, and its Nobel Prize-winning leader, are certainly sounding alarmed.

The G7 and the White House have both issued statements about a slide away from reform, with Joe Biden warning Mr Abiy over “the escalating violence and hardening of regional and ethnic divisions in multiple parts of Ethiopia”.

Ethiopian officials have hit back, indignantly, against western interference and “condescension”. A political tilt towards Russia and China – already a key economic ally – seems very possible.

Much now depends on Mr Abiy himself. Will he back down – the “pivot” some western diplomats say they’ve been promised by his aides – after the elections, and agree, at the very least, to improve humanitarian access in Tigray?

It seems hard to imagine any Ethiopian leader prepared to preside over a repeat of the 1984 famine.

But Mr Abiy’s critics point to what they say is a worrying trend of poor decision-making – from his handling of the growing diplomatic row with Egypt and Sudan over control of the River Nile, to the chaos in Tigray, to concern that neighbouring Eritrea – its army invited in to Tigray and accused of horrific human rights abuses – has deftly out-manoeuvred Ethiopia, to broader fears that Mr Abiy’s centralising tendencies are simply unsuited for such a complex patchwork of a nation at such a difficult time.

So, will this be an irrelevant sham election? A flawed, but significant step on the path to democracy? Or a catalyst for spiralling conflict? Right now, there is no country on the continent with more at stake.

Source: BBC