Some children who have grown up in Africa being forced to speak English are facing an identity crisis.

Khahliso Amahle Myataza’s family is from the South African township of Soweto in Johannesburg where they spoke Sotho, Xhosa and Zulu.

She would switch languages depending on who she was talking to.

But when Khahliso started primary school her family moved to a predominantly white neighbourhood of the city.

“I was severely bullied for not knowing how to speak English properly, for not knowing how to pronounce certain words,” she told the BBC.K A MyatazaTo learn English I immersed myself with white kids. I didn’t want to associate myself with the black kids any more. It was really difficult”Khahliso Amahle Myataza

South African student

There were other black children in a similar predicament but they didn’t make friends with each other – not wanting to be associated with others who did not speak English.

“To learn English I immersed myself with white kids. I didn’t want to associate myself with the black kids any more. It was really difficult.”

The 17-year-old’s fluency has come with the realisation of how, not only being able to speak English, but to speak it in a certain way – can open and close doors in South Africa.

“When I go to a restaurant with my mum, and they hear her speaking Xhosa or Sotho, they will automatically assume we’re not really here to buy expensive food.

“Then when they hear me or my brothers speak English, especially my brother, then we see people jumping.”

‘Pidgin banned’

For the parents of 22-year-old Nigerian Amaka, who asked us not to use her real name, this too must have been apparent.

When she was growing up in Lagos, English was the only language she was allowed to speak.

Her Igbo parents took her English language skills seriously and as a young girl she attended an etiquette class where diction was a key component of the lesson.

They also frowned on her using Pidgin, which is widely spoken in Nigeria as a lingua franca.

“I was watching a movie on TV and they said something in Pidgin English. And I kind of responded… and I got in trouble,” she told the BBC.

Their attitude was: “English is the only proper language”.

This was so engrained that Amaka says the fact that she could not speak Igbo did not bother her initially.

“I was very kind of proud of myself in being able to speak English language the way I can.”

But when she was about 15, she met her paternal grandmother for the first time – and they could not communicate or connect at all.

“That was the first time I realised that: ‘OK – this is an actual problem. This is a barrier.'”

‘Am I really black?’

And Khahliso says her relationship with her mother tongues has changed as she is now less proficient in languages like Sotho and Xhosa.

She’s unable to hold a conversation without turning to English words – an experience she describes as being “colonised by English”.

Khahliso believes her situation – and that of Amaka – are not unusual.

“A lot of black children in the middle-income class are facing that identity crisis of: ‘I can’t speak my native language.’

“I forced myself to unlearn it. Am I really black if I do not know how to speak my vernacular? Am I really black if I don’t know how to say: ‘I love you’ to my mum, in Sotho or in Xhosa, or in Zulu, or in Tonga?”

Amaka is working to overcome her identity crisis by taking Igbo lessons and immersing herself in Igbo culture through films and music.

“Language gives you a sense of community,” she says.

“It makes you see the world in a different light, it makes you feel like you are a part of something, something greater than yourself, something that has been there for generations, and will continue to be there for generations”.

Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has spoken about a linguistic famine in African societies – which he says is the result of prizing foreign languages over native languages.

Despite an estimated 2,000 languages being spoken across the continent there is still a tendency to see English and French – the languages of the countries which colonised most of Africa – as those needed to succeed and as a result some choose to abandon their mother tongue.

‘Only smart kids speak English’

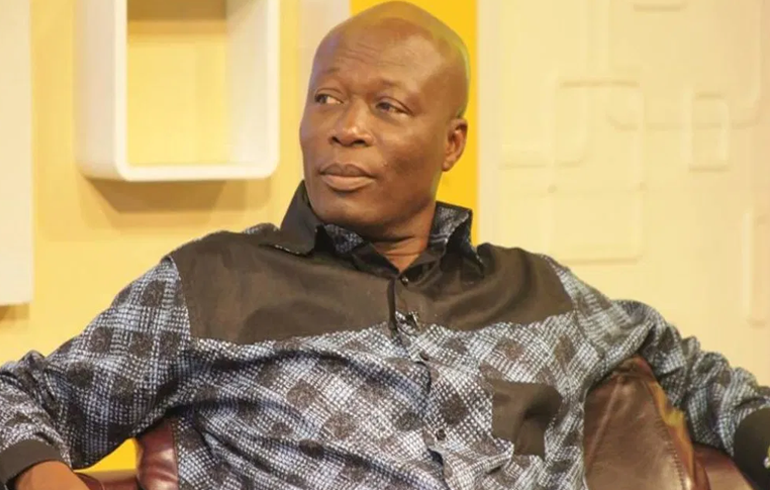

In Ghana, which like South Africa and Nigeria was colonised by the British, this attitude is prevalent, says Ronald – a secondary school teacher in a rural area who also asked us not to use his real name.

“There is this stereotype that the smarter kids are the ones that speak English. Even parents that never went to school try to force it on their children to also be fluent in English.

“I know quite a number of people that have never travelled beyond the borders of Ghana, but they can’t speak any language besides English.”

But he feels some students would perform better if some of the textbooks and the language of instruction was in their mother tongue – and that this would stop children dropping out of school.

“If I ask them a question, some of them would tell me: ‘Sir, I know the answer, but I don’t know how to say it in English.’

“Everyone is just trying to force them to speak this white man’s language and… some of the students then say: ‘It’s just not for me. It’s for the “smart” ones.'”

Khahliso says if she could go back in time, she would approach language learning differently.

“I would allow these languages to co-exist and to exist in one space – because they can co-exist. My sister and my friend are proof of that.

“To assimilate I don’t think that I needed to throw away my languages and to completely stop speaking Xhosa and Sotho.”