Yordanos Brhane was 15 years old when she fled Eritrea, crossing Africa and Europe in the hope of finding a better life and re-uniting with her family.

Years later, the long and difficult journey brought her to the UK, where she was fatally stabbed just months after settling. Yordanos’s sister has spoken about how a young woman’s dream of security ended in tragedy.

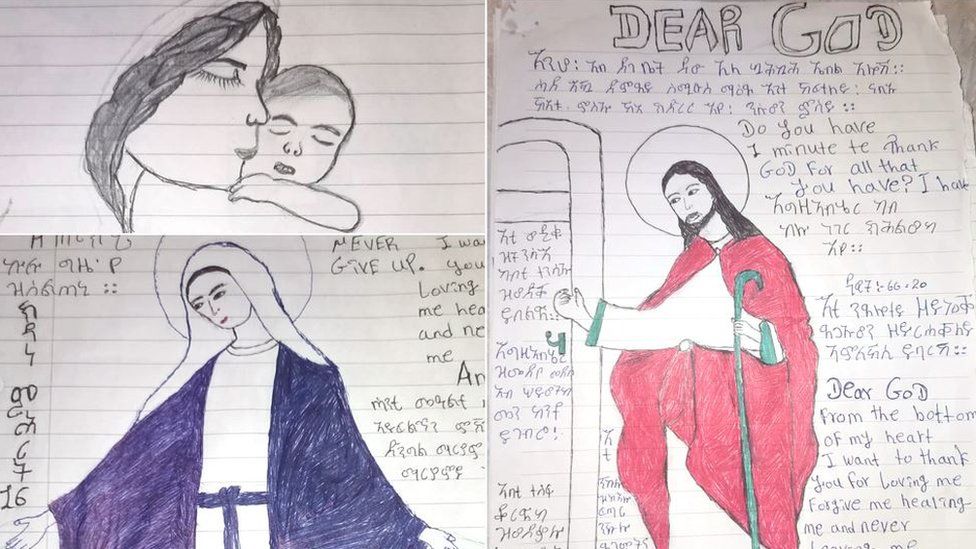

Deeply religious and with a flair for languages, Yordanos Brhane had just started to build a life for herself in Birmingham. She, along with six of her siblings, left Eritrea, one of Africa’s poorest countries and one where people regularly flee political persecution and forced conscription.

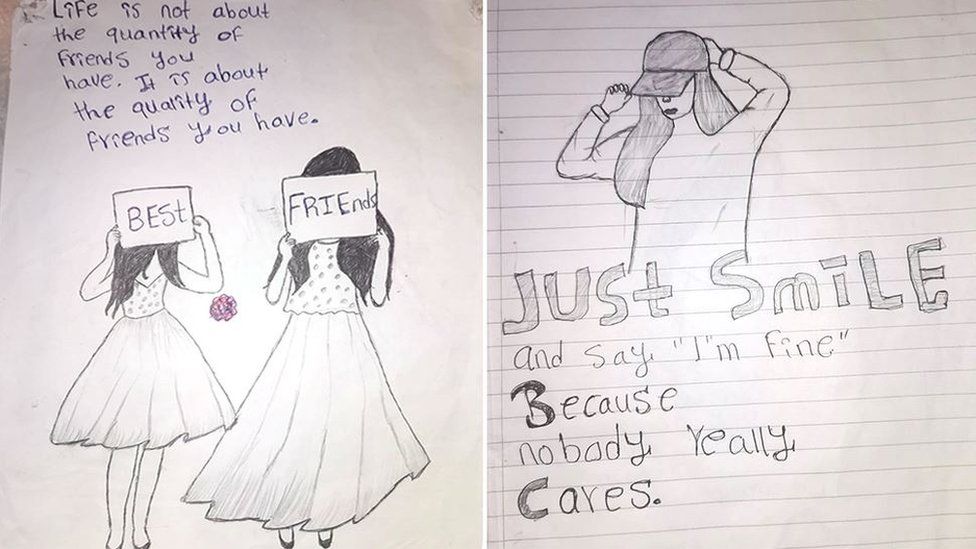

“Yordanos was a very quiet girl, she was polite, courteous, she was on the quiet side rather than very active,” Kisanet Brhane said of her younger sister.

“She was happy, she was learning the language very quickly, she was very good with languages. She had made friends from Eritrea and I sensed she was settling in nicely.”

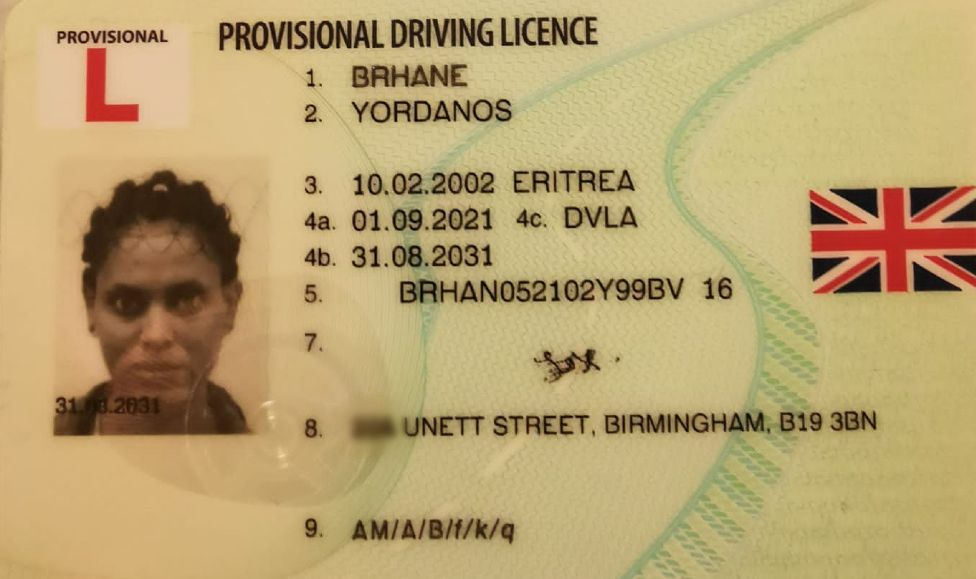

Her family, when they came to the shared house in Unett Street after her death, found she had joined the city’s library and had got herself a provisional driving licence.

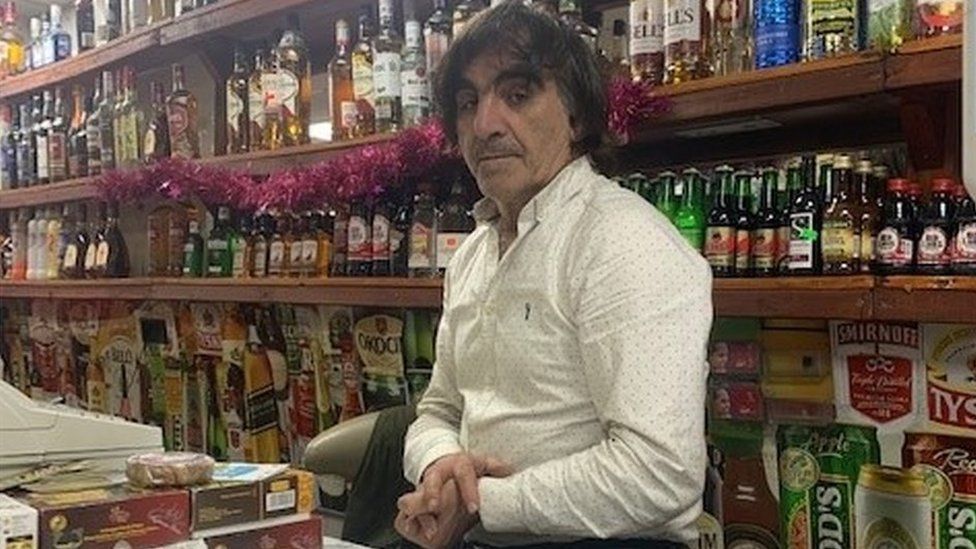

She had also found herself a job, helping out at a nearby shop where her manager, Sogi Omrani, said she was a beautiful and honest person who was always happy and smiling and all about helping her family.

“She was a nice worker. She had only been here a short amount of time but she talked so nicely. She was very good at English,” he said.

“All our customers, when they heard she had died, they were crying. I cried too, it was very bad.”

Kisanet was seven years older than her sister, but the two had a close bond.

“From the day that she left Eritrea until two days before she died, every day we were in contact, we were very close and every day I was speaking to her.

“The last two days of her life I hadn’t spoken to her.”

Kisanet lives in Norway, having left Eritrea in 2014, aged 19. Since moving there, she has studied, worked in care homes and recently gave birth.

Her own journey, which took her through the African countries of Ethiopia, Sudan, Libya and then the European countries of Italy, Germany, Sweden and Norway, took her a year.

Eritrea

- Became independent from Ethiopia in 1993 but is plagued by repression at home and tense relations with its neighbours

- Bordered by Sudan, Ethiopia and Djibouti, it occupies a strategically important area in the Horn of Africa

- Eritrea is a one-party state and a highly-militarised society, which the government has sought to justify by citing the threat of war with Ethiopia

- Prolonged periods of conflict and severe drought have adversely affected Eritrea’s agricultural economy and it remains one of the poorest countries in Africa

- By UN estimates, hundreds of thousands of Eritreans have fled the country in recent years, making the perilous journey across the Sahara and the Mediterranean to Europe

“The journey was very, very difficult, especially when crossing the Sahara Desert in Libya, it was the toughest, it was very, very tough, its not easy at all – you risk your life to go through this journey,” she said.

In March 2017, aged 15, Yordanos began the same arduous journey.

Her journey was similar to her sister’s but took longer. She was in Libya for seven month where, her sister says, it was a miracle she got out alive.

“She didn’t have a good time there it was very, very dangerous, very bad, she experienced really bad things,” she said.

Yordanos and her fellow travellers slept on floors in warehouses, among hundreds of people, with no privacy, a scarce amount of food and no access to medication or sanitary hygiene, she said.

The threat of violence and rape was always prevalent. Kisanet believes it was only because by then Yordanos was so weak and ill she was not assaulted.

By the time Yordanos got into Europe, she was very ill indeed, arriving into Italy on a stretcher.

She had been rescued by the authorities after the boat she came across on, via smugglers, stopped working in the middle of the ocean.

“Her illness was mainly due to malnourishment and very bad scabies infections in her skin which had given her a fever. She had bad problems with her chest, her heart was beating very hard,” Kisanet said.

“She was really weak by the time she arrived in Italy. We didn’t find out straight away she was in Italy – two weeks later we found out she was in hospital where she was getting treatments to get her energy back and help her survive.”

But as she was being given treatment to get her better, other problems were about to begin.

Yordanos managed to make it to Norway where she was allowed to spend time with Kisanet as well as living in a camp.

However, while going through the process it was discovered she had been ‘fingerprinted’ in Italy.

According to regulations, the first country an asylum seeker enters is ultimately responsible for the individual’s asylum application. In effect, officials could tell her first EU country of entry was Italy and could be the one she would be returned to.

And that is what happened – the authorities in Norway decided to return her to Italy. The sisters were shocked.

“She had been really happy, she was in a safe environment where human right is protected,” Kisanet said.

“She was really serious about her education and she improved her language so well. I have lived here two years ahead of her, I couldn’t speak better than her.

“She was really optimistic about life and she didn’t expect to be sent back to Italy.”

The news was hard for them both to take in.

“Especially as her age, she was only 16, I was older than her, I could have taken care of her, I was her family, her sister. What they did was wrong. She was only 16. To be separated from her family at that age.”

Yordanos was taken back to Italy within the week, leaving the family with little chance to appeal.

After a few days living rough and begging for food, she made the journey to Belgium and made contact with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), which, because of her age, picked up her case and began to argue she should be able to return to Norway.

Norway accepted her return, while her case was being resolved, and again she stayed with her brother, who lived in a different part of Norway, and also in a camp.

“After three months the charity gave her the letter to take to police to say she is back from Italy and she has this letter to say she should have her case looked at properly,” Kisanet said.

“But the police put her in prison for two months. They would not let her go. They said they did not accept it and that she should go back to Italy. She was forced to return to Italy.

“It was the same situation, she was left to fend for herself at such a young age. It was very distressing for her.”

Her lawyer in Norway, Andre Mokkelgjerd, said the Dublin Regulation, which regulates which country is responsible for processing an asylum application, does have discretionary clauses which made it possible for Norway to consider allowing her to remain – particularly as she was a vulnerable young woman alone in Europe with family in Norway.

“Unfortunately, our arguments along these lines were not given decisive weights, and the general rules were applied strictly as they often are in these cases,” he said.

Yordanos went back to Belgium, living rough, for seven months; although Kisanet says she did get help from some Belgian charities. And when she eventually made it to the UK, on the back of a lorry, the charity workers stayed in contact.

“They were really nice, very close to Yordanos, and they were happy she came to a safe country. They came to visit her twice,” Kisanet said.

After a year in the UK, Yordanos was granted to leave to remain with refugee status. She was 18 when she arrived.

The family found out she had died through social media.

“I didn’t know what happened, it was my sister who contacted me, she had seen something on Instagram.

“She said ‘what am I hearing – have you spoken to Yordanos?’ and I said ‘no I haven’t spoken to her for two days, what happened?'”

Kisanet and her husband were able to contact some of Yordanos’s friends. They heard Yordanos was no longer alive, there had been an accident. They later had to come over to the UK to identify the body.

“With the shock of the news, we quickly arranged for three siblings including myself to come to the UK to identify the body.

“When we arrived, there were a lot of Eritrean community helping us out. They prepared accommodation where we could stay and they were very helpful to us,” she said.

She was unable to make the journey for Yordanos’s killer’s court case. Halefom Weldeyohannes, from Sheffield, has been jailed for at least 21 years for her murder.

But the family said 21 years was not enough.

Yordanos’s older brother Gezae Birhane Kibedom said: “I am not happy, Yordanos was a nice girl. He hurt my sister, he took a life, it’s not enough.”

He had been in contact with Yordanos three days before she died. She told him she had started to learn to drive and also her plans for the future.

“She wanted to go back to school, she wanted to become a doctor or a nurse and then ultimately she wanted to go back to Eritrea where, depending on the government, she would try to help our family and other young people.

“Yordanos was so young but old for her age.”

Source: BBC