Bernard Looney had a great first day in his new job as chief executive of oil giant BP. We know this because he took to Instagram on Wednesday to tell us, posting a video of happy, smiling employees at one of the company’s operations in Germany.

We also know that Tidjane Thiam, boss of financial giant Credit Suisse, is worried about those suffering from coronavirus. Under an image showing Chinese President Xi Jinping – one of many pictures Mr Thiam posted of himself hobnobbing at last month’s Davos World Economic Forum – he says solemnly: “Our employees’ health and safety is our top priority.”

Once the preserve of young people posting pictures of their lunch, Instagram is becoming part of the the corporate world’s marketing machine.

The app was where many of us turned to escape thoughts of work. Now it’s where your company can boast about all the good deeds it does in the community, or where the boss can voice concerns over their employees’ mental health.

‘Dad dancing’

Sara Tasker, an influencer and Instagram consultant, gives companies ten-out-of-ten for effort, but is less than impressed by the execution. She tells the BBC: “There is a slight sense of a dad dancing at a wedding when you see these chief executives posting on social media.”

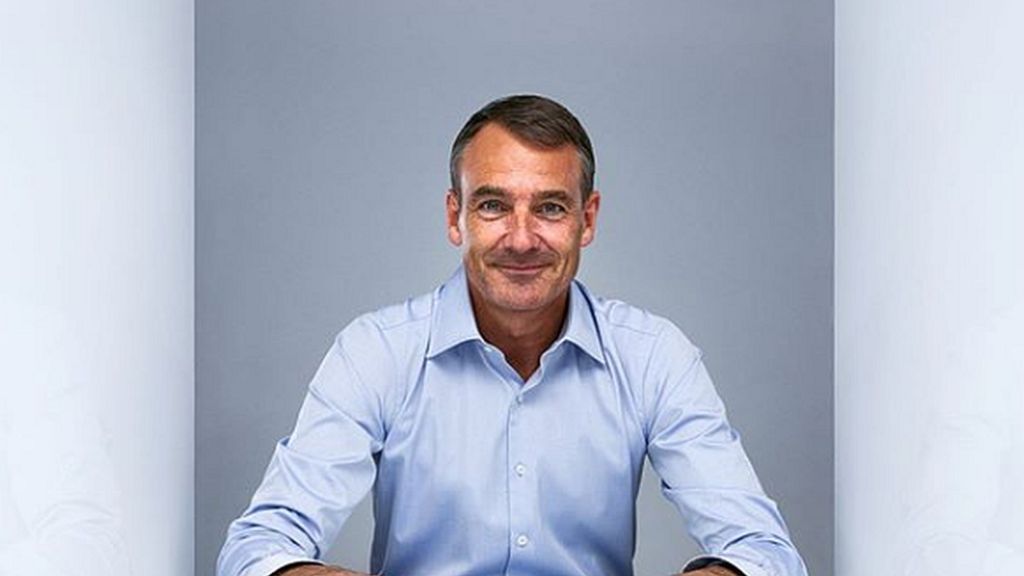

BP’s Mr Looney is a newcomer to the platform. As of Thursday morning he had posted six times, but had already accrued 3,533 followers. Clearly none of them were from Greenpeace, which turned up at BP’s central London headquarters on Wednesday hoping to disrupt his first day at the office when Mr Looney was some 500 miles away in Germany.

The boss of Spanish bank Santander, Ana Botín, has been on the Instagram platform a few months longer. Her account now features 272 posts, both in English and Spanish.

But much of the content follows a familiar corporate formula: get yourself pictured in exotic locations and show plenty of corporate social responsibility. Climate change, micro-finance, healthy living and sustainability are all present and correct.

But she also finds room for some atmospheric pictures of London’s Hyde Park – “one of my favourite cities” – and similar shots in Madrid’s Retiro park.

There is a sense with some of these Instagam newcomers that they are dipping their toes nervously into a world they do not quite understand. In his first post, Mr Looney writes: “I’ve long been a fan of Instagram, but mainly in the background, so here goes with a new approach!”

Alongside a picture of himself – wearing a navy jumper with his hands half tucked in to his jeans pockets – he says: “I look forward to sharing what I am up to, who I am meeting and offering a window into the decisions, challenges and opportunities that are ahead.”

He said he wanted to use the platform to talk “openly” about people’s concerns over the oil and gas industry. “I encourage you all to be candid – I consider honest and open discussion crucial,” he wrote.

Ms Tasker says, done well, Instagram can be a great vehicle for giving people a behind-the-scenes glimpse of what they do.

“It’s a difficult one – if you can do it well, it’s a great investment of your time and energy but it often means compromising on some of the PR machine that chief executives like,” she says.

“People are looking for a bit of authenticity and a connection they can’t get elsewhere so you really need to share something above and beyond what you put on traditional communication channels.”

It’s about putting a human face on the business, says Alexei Lee, a communications adviser at marketing firm Reading Room. But he says there’s always a risk the executive might post something that creates a social media storm about something that does not represent the company.

He suspects there are PR people working behind the scenes running these executives’ social media accounts. As BP itself is only too well aware, shooting from the lip has serious consequences.

Amid BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig disaster, then boss Tony Hayward made several gaffes, including saying “I want my life back” when asked about the personal toll of dealing with the crisis that killed 11 people. Luckily for Mr Hayward, social media was in its infancy in 2010, but the critical fall-out was huge and Mr Hayward’s days at BP were numbered.

‘Contentious’

So, why take the risk? A big reason is the desire to connect with younger employees – and younger people in general, says Dave Endsor, who works for Tank PR.

But he’s sceptical they can win the hearts and minds of the younger generation by muscling in on their own turf (or platform).

He, too, says the struggle to sound authentic could be insurmountable. “It’s less authentic than someone who’s got more of an engagement with the community, whether that is Melinda Gates or Arianna Huffington,” he says, referring to the philanthropist and businesswoman.

And BP is a prime example. The oil giant is a “contentious” business and trying to meet the likes of Greta Thunberg and her followers on the platforms like Instagram “could blow up in Mr Looney’s face,” said Mr Endsor.

BP did not respond to an emailed list of questions.

Mr Looney did not respond to an interview request sent on Instagram.

Source: BBC